|

| A mountain in Galilee overlooking farmland. Much of The Bronze Bow takes place in this setting. |

When I think about

The Bronze Bow, by Elizabeth George Speare, I don't think of reading it. I think of living it. I was right there with the hero Daniel on the mountain above his village in Galilee, in the blacksmith forge in the village, and in the presence of Jesus, who is a character in this book. I had no consciousness of reading or of the writing. The writing dissolved into an experience of Daniel's journey into adulthood.

The Bronze Bow is a hero journey--Daniel starts out as an angry adolescent, alienated, in hiding. As is typical of a hero journey, he undergoes trials and temptations, gains tools for his quest, and transforms into a strong man of love and understanding.

|

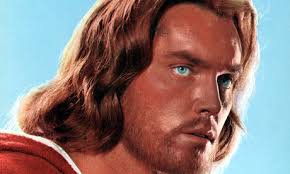

Here's Jeffrey Hunter as Jesus with his strangely

glowing gentile blue eyes. From King of Kings. |

The book takes place at the time Jesus was preaching in Galilee--shortly before his journey to Jerusalem. As in

Ben-Hur, a book also reviewed in this blog, the Jews of the time were looking for an earthly king to lead them in overthrowing their Roman occupiers. One of Daniel's friends is a Zealot named Simon, who has made it his mission bring freedom to the land. After fleeing his village, Daniel is befriended by another band of rebels led by the warlord-esque Rosh, who lives off the land (meaning he pillages the local farms and fields). Daniel believes that Rosh will be the one who throws off the Roman yoke.

The most important gift of Daniel's hero journey is a set of friends--Joel and Thacia. For the first time, Daniel has someone with which to share his hopes, his dreams, and his story. Daniel's life has been harsh, filled with violence, losses, and poverty. The camp of Rosh seems like luxury to him--plenty of food, a warm fire, a mission to perform. Joel and Thacia enlarge Daniel's view of the world and bring him face to face with some of his prejudices.

|

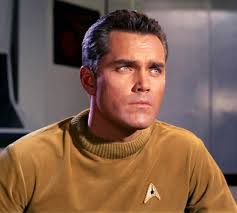

In addition to playing Jesus in King of

Kings, Jeffrey Hunter played an equally

intense James T. Kirk in the pilot episode

of Star Trek. Those limpid eyes! |

Daniel's friend Simon invites Daniel to hear Jesus preach at the local synagogue. Jesus is somewhat romantically presented, like the Jesus portrayed by Jeffrey Hunter in the movie

King of Kings. Even the camera seems to have its breath taken away whenever Jesus is shown in that film. In

The Bronze Bow, Jesus has a magnetism about him, and a magical voice, and a huge amount of somewhat fevered charisma. In other words, he is not portrayed as a man, but as an already-god. As with Ben-Hur, Daniel wishes Jesus would use his powers to call together an army and to establish an earthly kingdom. Like Ben-Hur, Daniel must come to terms with the idea of a heavenly kingdom, a kingdom of the heart and soul.

I think Daniel's conversion is somewhat elided. It doesn't make logical sense in terms of the story. It sort of happens because it is supposed to happen, because if you meet Jesus it must happen. And, I know that religious conversion is not necessarily logical, but a novel must play itself out in certain ways and this one doesn't. However, that is the only flaw I find in this book, and less critical readers will probably be OK with Daniel's change of heart. And I was glad for it. He was so miserable. Still, how would his situation have been resolved in a purely Jewish context? People from all faith traditions deal with developmental crises. I guess it bothers me a little bit that the only solution presented for Daniel was Jesus. I worry that Christian writers don't fully take into account the seriousness and cultural dissonance of a conversion of a Jew to Christianity. It makes me a little queasy.

|

Daniel's sister is a weaver. The weaving seems to be her

way to bring order to her disordered psyche. |

The book is deeply humanized by the character of Daniel's sister Leah. Her response to the losses and violence was withdrawal rather than anger. Over the course of the book, she is brought out, drawn out, by Daniel, by Thacia, by a Roman soldier, and eventually by Jesus, who cures her of her maladies. Her gradual reaching out into the world is beautifully drawn; and Daniel's relationship to her illuminates him also.

The Bronze Bow is a book rich with love and the conflicts that love sometimes brings about. How much sacrifice is too much sacrifice? How does being true to oneself relate to sacrifice? When is love not enough? What is healing? What is a commitment? These are big questions and they are addressed in this book. They are the questions of fine literature and so are appropriate to this fine book. I am still amazed that the writing in this book sort of disappeared in the experience it was describing. That's a huge accomplishment and I salute Elizabeth George Speare for it.

I have a few more books by Speare on my list. I'm very interested now in how they will strike me. Is the transparency of Speare's writing particular to

The Bronze Bow? I can't wait to find out.