Knockemstiff, by Donald Ray Pollack

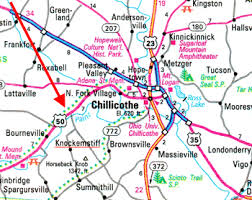

Knockemstiff is a collection of short stories written by a Ross County, Ohio, author about a Ross County, Ohio, town. I have been through Knockemstiff. My dad and indeed many of my ancestors were born and raised in Ross County. I've been on a genealogy quest lately and am surprised, truly, by how many of my forebears lived in this very part of Ohio where I live now as early as the 1790s. One of the key towns in many of the Knockemstiff stories is Massieville, in whose cemetery many of my relatives are buried, including my paternal grandmother, Bessie Ann Grow Burns Dickerson. So, the landscape of these stories is very much my own landscape and many of my relatives followed the life path of the characters.

Knockemstiff is a collection of short stories written by a Ross County, Ohio, author about a Ross County, Ohio, town. I have been through Knockemstiff. My dad and indeed many of my ancestors were born and raised in Ross County. I've been on a genealogy quest lately and am surprised, truly, by how many of my forebears lived in this very part of Ohio where I live now as early as the 1790s. One of the key towns in many of the Knockemstiff stories is Massieville, in whose cemetery many of my relatives are buried, including my paternal grandmother, Bessie Ann Grow Burns Dickerson. So, the landscape of these stories is very much my own landscape and many of my relatives followed the life path of the characters.

There are 18 stories in this 200-page book, so they really are short. (Nothing like long short stories...) And at first, I was repelled by them. The content and characters are both pretty ugly. Thieves, murderers, drug dealers and abusers, sexual deviance, family violence, grizzly pasts and grimmer futures. Knockemstiff is a dying town (and could, in a negative region-view, represent dying Appalachia itself) where the underclass is what remains...people who, unlike Gertie in The Dollmaker, just can't make the transition to an acceptable life.

There are 18 stories in this 200-page book, so they really are short. (Nothing like long short stories...) And at first, I was repelled by them. The content and characters are both pretty ugly. Thieves, murderers, drug dealers and abusers, sexual deviance, family violence, grizzly pasts and grimmer futures. Knockemstiff is a dying town (and could, in a negative region-view, represent dying Appalachia itself) where the underclass is what remains...people who, unlike Gertie in The Dollmaker, just can't make the transition to an acceptable life.

However, Pollack succeeded in making these people real to me, and awakening not sympathy, but at least a bit more understanding. By the middle of the book, I could see that the stories formed an arc of some sort, tracing the pathologies of generations mutate and transmutate in expected and unexpected ways. He also records a street history of drugs abused over time, culminating in the current prominence of prescription painkillers.

However, Pollack succeeded in making these people real to me, and awakening not sympathy, but at least a bit more understanding. By the middle of the book, I could see that the stories formed an arc of some sort, tracing the pathologies of generations mutate and transmutate in expected and unexpected ways. He also records a street history of drugs abused over time, culminating in the current prominence of prescription painkillers.

The people in these stories are people I am very interested in. How do you offer hope and help to the people I work with when the world they know is so stark? How do you offer hope and help with respect? I often think that help is often a slap in the face, a belittling action, a judging action. It's my favorite butter on cold toast analogy coming up again. How does alcohol and drug rehab work when people get clean but return to a town where there are no opportunities?

The people in these stories are people I am very interested in. How do you offer hope and help to the people I work with when the world they know is so stark? How do you offer hope and help with respect? I often think that help is often a slap in the face, a belittling action, a judging action. It's my favorite butter on cold toast analogy coming up again. How does alcohol and drug rehab work when people get clean but return to a town where there are no opportunities?

I was interested in Pollack's portrayal of how prescription painkillers invaded the Knockemstiff area. They became a way of life. In one story, a couple drains the woman of blood every month (visiting several plasma centers in a single day) to keep stocked with painkillers. By taking these people seriously Pollack gave them some dignity.

I was interested in Pollack's portrayal of how prescription painkillers invaded the Knockemstiff area. They became a way of life. In one story, a couple drains the woman of blood every month (visiting several plasma centers in a single day) to keep stocked with painkillers. By taking these people seriously Pollack gave them some dignity.

I was reminded a lot of Faulkner when reading these stories. He, too, dignified the ugly, the profane, without mocking. In one of Faulkner's books a character falls in love with a cow. And you don't laugh.

Knockemstiff is not for the faint of heart or the over-sensitive. It is graphic and grim. The writing is terrific, though. Vivid descriptions, settings painted on the screen of the mind, smells, sounds. I don't think I was aided much by having driven through Knockemstiff, because these stories took place off the highway, inside barricaded homes, in caves, in trailers, in cars, in hollers, creek beds. The bleak inner landscape of the characters was recorded in their bleak structures. They could only live within what they knew. You can't really do anything else.

The people in the Knockemstiff stories are my neighbors, relatives, and friends. I must honor even their squalor, somehow. These stories help.

The Sign of the Beaver, by Elizabeth George Speare, will leave you feeling very sad because it is a very good book. Though it is told through the eyes of a white boy, the book illuminates the crisis of America's native people. If it were not written so well, your heart would be in less danger.

The Sign of the Beaver, by Elizabeth George Speare, will leave you feeling very sad because it is a very good book. Though it is told through the eyes of a white boy, the book illuminates the crisis of America's native people. If it were not written so well, your heart would be in less danger.

Set in the 1760s in the remote woods of Maine, The Sign of the Beaver tells the story of 13-year-old Matt, who is left in charge of his family's farmstead while his father returns to their former home to fetch the rest of the family. Matt is well instructed for, though fearful of, his long summer alone. His father gives him a set of sticks to notch--seven notches on each stick. After six sticks, he can look for his father to return.

Within two weeks, trouble comes knocking--or, rather, bursts through the door of Matt's cabin. Much of his food and weaponry is lost and he becomes dependent on fishing every day for his meals. Trekking out to his fishing spot, he often feels like he is being watched. After an accident with a bee tree, it turns out Matt was right. Two Indians--an old man and a boy--rescue him and return him to his cabin. The trio become friends.

Attean and Matt learn much from each other and come to understand both cultures from a different perspective. Matt, especially, sees how it seems to the Indians for more and more white people to move into their hunting areas, how that encroachment threatens their survival.

The book's setting is beautiful... much of it I imagined as woods I have been in, creeks I've followed, deer I've seen. When I am out in the woods, I am aware of how much I do not understand about the interactions of all of its living and nonliving aspects. I am in the woods, but not of the woods, although I have approached "of" a couple of times. Attean and his grandfather give Matt (and us) a glimpse of "of."

The book's setting is beautiful... much of it I imagined as woods I have been in, creeks I've followed, deer I've seen. When I am out in the woods, I am aware of how much I do not understand about the interactions of all of its living and nonliving aspects. I am in the woods, but not of the woods, although I have approached "of" a couple of times. Attean and his grandfather give Matt (and us) a glimpse of "of."

As in The Bronze Bow, the writing completely disappeared from this book. It was like all of my surroundings--reclining chair, dozing cat, furnace humming, the weight of the book, and the words on its pages--just fell away, leaving me in front of a cabin in thick forest and alone. Somehow, Speare's writing cuts through layers and layers of awareness into the experience of a fictional world. Excellent. I again pay tribute to Speare's skill and giftedness. She did it again.

I appreciate that Speare did not take sides in the whites vs Indians issue. She merely portrayed what happened. As whites moved into the Maine woods, less game was available for the native people living there. They had to move to maintain their way of living or assimilate into foreign ways or fight. The fighting of the French and Indian War had just ceased...that was not the choice of Attean's people.They moved. It reminded me of the ending of the outdoor drama Tecumseh when, at the end, the Indians leave, moving slowly to the west (and at the amphitheater, it is actually west) and into death. It's one of the saddest images I know, a kind of fall from paradise, but through no sin of the faller. It's like Adam and Eve had been kicked out of the garden by squatters. (And reminds me of Faulkner's Snopeses, who infiltrated and mocked the mythical South.)

At the end of this book it is winter and when I re-emerged from the book I found that it had been snowing. I awoke into Matt's world and had to shake myself free. That's a good book, when you have to shake off one reality for another.

SIDEBAR: Tecumseh Outdoor Drama

SIDEBAR: Tecumseh Outdoor Drama

The outdoor drama Tecumseh is performed every summer in Chillicothe, Ohio. To find out more, go to www.tecumsehdrama.com. It's an amazing pageant and drama and lots of fun.

SIDEBAR: Man's Worlds

It's funny to me that both The Bronze Bow and The Sign of the Beaver take place in a boys' and men's world. Female characters are somewhat ancillary, even with the inclusion of the sister and girlfriend in The Bronze Bow. In both books, women are noticed and their work is respected, but the action of both books is decidedly male. From her biography, I cannot tell whether this maleness is a common thread throughout her work. Her most famous book, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, is about a girl. It is on my list and I will read it as soon as I can procure it.

SIDEBAR: Where is your frontier?

I love that The Sign of the Beaver is set in the 1760s. Being an Ohioan, my frontier of interest is the pre-Western frontier...the settling of the Appalachian area rather than of the Great Plains and West. My war is the Revolution, not the war between the states. In an old tree identification book I have, Ohio is considered "the western lands." I have a fascination with the 1750-1800 time period and with Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton, adventurers who walked alone through my land, the land of my ancestors (at least as far back as about 1840). They walked alone through the pre-Columbian paradise and didn't even know it--they probably just saw a bunch of dollar signs or Christian settlements or utility. I don't know. But this book was right up my alley.