The Dollmaker takes place against a backdrop of World War II. The war takes all the men away from her community. This disruption in the life of subsistence farming is dramatic and leads to the eventual depopulation of Appalachia. Waiting for news becomes the focus of the women left behind. Gertie's husband must choose between evils--the army or the factory. He chooses the factory, which is better for his family. The irony of this decision drips through the book, as his family suffers.

More people came down the lane: children running, women with babies in their arms walking tiredly, old women like Sue Annie, hurrying, with no wind left for gossiping. They would see her and forget the old greetings of other days like, "How's your mother a holden up, Gertie?" or, "Law, law, it's been a time an a time since I've seen you. When are you a comen to stay all day?" Instead, they all, young and old, asked with breathless abruptness, "Has the mail got in?" (pages 151-152)

In the course of a day, Gertie's world rocks on it foundations. She follows her husband to Detroit, Michigan, where he has taken a job in a steel mill in lieu of going into the army. She moves into ticky-tacky cheek-by-jowl worker housing in a filthy neighborhood next to the factories and an extensive network of railroad tracks. Noise, light, smoke, traffic, yelling, neighbors arguing on the other side of paper thin walls--these assault Gertie, a cacophony of ugliness.

The steamy, nasty smell of the drying, half rotten reused wool mingled with the gas smell, the chlorine water smell, the supper-getting smell, and became one smell, a stink telling her it was the time of day she had learned to hate most. The time she had loved back home, the ending when the day was below her. (page 265)

It took Great Britain and North America more than 100 years to accomplish what Gertie did in a few weeks--obliterate the agrarian and adjust to the mechanical. Gertie's experience reminds me of tales of isolated villages in the Amazon basin who come into contact with modernity for the first time. We like to see them as amazed, but, like Gertie, they might just be horrified.

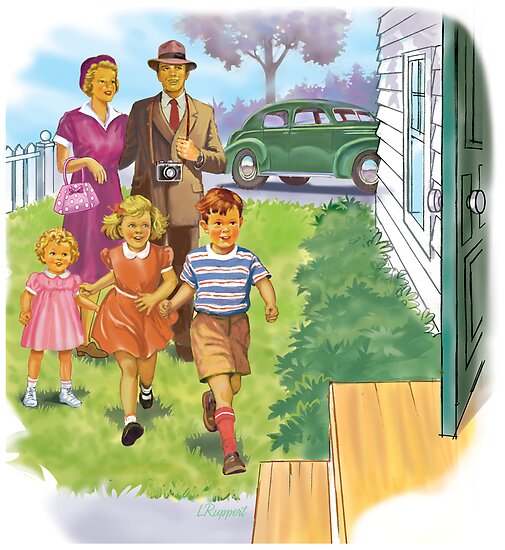

The Dollmaker can be viewed from so many different angles that I actually have a list--and it is about 25 items long. One of the key perspectives is the immigrant experience. The work force in Detroit comes from around the world and many of the people have no point of reference for city life. People from the Appalachian region were doubly alienated--as clueless as any immigrant but without the expectation of strangeness. Gertie had no reference point for the environment she moved to and was disoriented by how badly the new environment completely unmet her expectations. Many of her expectations were form from primary grade readers her children got from school back home--happy, helpful policemen; pretty streets with rows of trees; nice manicured yards around every house; sidewalks.

The Dollmaker can be viewed from so many different angles that I actually have a list--and it is about 25 items long. One of the key perspectives is the immigrant experience. The work force in Detroit comes from around the world and many of the people have no point of reference for city life. People from the Appalachian region were doubly alienated--as clueless as any immigrant but without the expectation of strangeness. Gertie had no reference point for the environment she moved to and was disoriented by how badly the new environment completely unmet her expectations. Many of her expectations were form from primary grade readers her children got from school back home--happy, helpful policemen; pretty streets with rows of trees; nice manicured yards around every house; sidewalks.The real butter, that was to have been a Christmas treat with hot biscuit, had got so hard and cold from its stay in the Icy Heart (fridge) that it refused to melt even on the hottest of the biscuit, and butter and biscuit were chilled together. Clytie (oldest daughter) had put the lettuce in the wrong place, and it was frozen. Reuben (son) complained the milk was so cold it hurt his teeth. Clytie blamed it on Enoch (another son), who'd turned down the cold controls; Enoch was angry; and Clovis (husband) turned sorrowful because the Icy Heart, like Cassie's new doll and the other things he'd bought, was unappreciated. (page 288)

I have also heard that at times in the past quarantine of Appalachian peoples onto reservations was considered. Surely, the population of the region is dwindling due to substance abuse, poor medical care, and economic hardship--some of the same conditions prevalent on Indian reservations. I'm fascinated by this kind of observation. I see myself as part of a fragile population and fragile culture, both of which are at risk of winking out.

...She had wasted Clovis's money for rotten bananas and poor meat and all the other things they didn't know about--the box of pepper half full, the rotten eggs, the rotten oranges, the sweet potatoes bought as a treat one night but all black in their hearts, yet showing no sign from the outside...She gripped the door handle. She could raise bushels of sweet potatoes, fatten a pig, kill it, and make good sausage meat, but she didn't know how to buy. She could born a fine and laughing boy baby and make him grow up big and strong, but inside him all his laughter died. (page 350)

I've heard Appalachian speech most of my life and can pop out with a good one every now and then to this day. I just have to channel my grandparents and aunts and uncles. My mom got trained in "proper" speech and struggled to sound "right." From her I got a grounding in standard speech. Speaking proper has always been a help (holp) to me. If I had sounded Appalachian when I went to Ohio State my experience might have been very different.

In addition to speaking a different dialect, Gertie also suffered from being taciturn--she was not talkative. She struggled to find words for objects and phenomena she had not conceived of before moving to Detroit. She struggled just like any other non-English-speaking person. I remember feeling that way when I went to Germany. Even the German words I knew were hard to produce. I just couldn't get them out.

Gertie spoke most eloquently with her hands and a knife. She carved wood, or whittled, as she called it. Whittling, though, as a connotation of frittering, killing time; whereas Gertie was a gifted artist in wood. She had a log of straight-grained cherry, maybe 18 inches tall and 18 inches across. Somehow, in spite of working 18-hour days, she found time to work on this log--to make an image of Jesus. Or was it Judas? She wasn't sure whose face would emerge from the wood. At the start of the book, only the top of the head has been carved. By the end of the book, the statue is complete except for the face. The insights Gertie gains from working on this piece of wood are the crux of the story. Images of Jesus include a vision of a laughing Jesus that came to Gertie right before her rural life ended; a shrunken and suffering Jesus on the cross on the crucifixes she saw in her Detroit neighbors' homes (she had never seen a crucifix); and various other bland and sober depictions.

She missed him, but could never tell him how she missed him most. She hated herself when she lied, trying to make herself believe she missed him the way a mother ought to miss a child. In the old song ballads mothers cried, looking at tables with empty plates and rooms with empty beds. But how could a body weep over a table where, even with one gone, there was yet hardly room for those remaining. The gas pipes were still overcrowded with drying clothes; and eight quarts of milk instead of ten in the Icy Heart meant only less crowding, not vacant space. Two pounds of hamburger cost less than two and a half and-- She would hate herself for thinking of the money saved, and try never to think that living was easier with no child sleeping in the little living room. (page 369)

Gertie's statue of Jesus shows that he is holding something. Is he taking it? Is he giving it back? Is it running through his fingers? What is it? The answer Gertie recieves forms the final apotheosis of the book. It was an answer I didn't understand when I read this book 30 years ago. My new understanding did not lessen the impact of the act. It was consistent with Gertie's inner understanding.

...it seemed so long ago that she had felt as that woman felt now--going to a place that would be paradise. Paradise: it was a pretty word. She'd never thought how pretty it was until now. When the woman spoke it in her soft rich voice, it made her think of peaches, pure gold on one side, red in the gold on the other, soft, juicy, warm in the August sun, warm-tasting like the smell of the muscadines above the river in October. "It's a pretty name," and remembering, twisting the hurt inside her, she said to the woman what she had said to herself, "'This day thou shalt be with me in paradise.'" The woman laughed. "That's what mah man said to me, only in different words." Gertie nodded, and her voice was defiant. "I'll allus think that a body oughtn't tu have tu die first to git it--that is, at least for a little--a paradise on earth."

Leaving Eden. Going among the world. Making a supreme sacrifice. Gertie's story parallels that of Jesus. Arnow uses the imaginary friend of Gertie's youngest daughter, Cassie, to deepen this theme. Cassie and her "friend" Callie Lou are best friends and go everywhere together and process Cassie's experiences together. To Gertie, this is for the most part harmless. But in Detroit, it is seen as crazy and odd. Gertie knows she should help Cassie adjust (a loaded word in this book) by, as she sees it, killing off Callie Lou. She must force Cassie to give up her own version of the laughing Jesus. The consequences of this action are heart breaking.

And, there is beauty in the filthy and crowded Detroit slum. It is in the faces of the children and the kindness of the people to each other. Even those who wish to remain apart end up as participants in the life of the alley. As Gertie's painter neighbor observes:

"Always I hated it, this alley, the ugliness, the noise--there wasn't time or quiet in which to paint--and of course nothing to paint. I never saw them--the pictures; Wheateye [little girl] standing on the coalshed roof with a popsicle in her hand...strange, I never saw her then, but I do now; dirty with popsicle juice dribbling down her chin; there'd be flies buzzing round, and the gray houses and the dirty trash cans, always spilling, and the back steelmill smoke, but there she would stand on the coalhouse looking up at the clean, silvery airplanes...But I never saw her." (pages 440-441)

You know me and endings. Well, the ending of The Dollmaker was great. I don't mean happy. I mean that Arnow saw the ending, wrote it, and stopped. She left it in our hands as it was. Now I have to carry that act of Gertie's as part of me. I am changed by it. That's a magnificent ending.

No comments:

Post a Comment